Getty Images

Getty ImagesJust weeks ago, Gautam Adani, one of the world’s richest men, celebrated Donald Trump’s election victory and announced plans to invest $10bn (£7.9bn) in energy and infrastructure projects in the US.

Now, the 62-year-old Indian billionaire and a close ally of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose sprawling $169bn empire spans ports and renewable energy, faces US fraud charges that could potentially jeopardise his ambitions at home and abroad.

Federal prosecutors have accused him of orchestrating a $250m bribery scheme and concealing it to raise money in the US. They allege Mr Adani and his executives paid bribes to Indian officials to secure contracts worth $2bn in profits over 20 years. Adani Group has denied the allegations, calling them “baseless.”

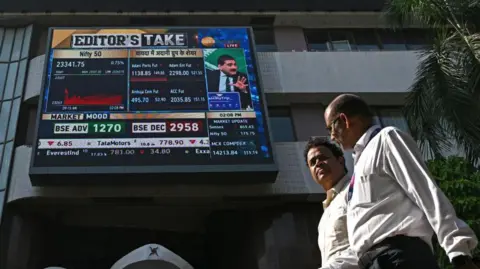

But this is already hurting the group and the Indian economy.

Adani Group firms lost $34bn in market value on Thursday, reducing the combined market capitalisation of its 10 companies to $147bn. Adani Green Energy, which is the firm at the centre of the allegations, also said it wouldn’t proceed with a $600m bond offering.

Then there are questions about the impact of the charges on India’s business and politics.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIndia’s economy is deeply intertwined with Mr Adani, the country’s leading infrastructure tycoon. He operates 13 ports (30% market share), seven airports (23% of passenger traffic), and India’s second-largest cement business (20% of the market).

With six coal-fired power plants, Mr Adani is India’s largest private player in power. At the same time, he has pledged to invest $50bn in green hydrogen and runs a 8,000km (4,970 miles)-long natural gas pipeline. He’s also building India’s longest expressway and redeveloping India’s largest slum. He employs over 45,000 people, but his businesses impact millions nationwide.

His global ambitions span coal mines in Indonesia and Australia, and infrastructure projects in Africa.

Mr Adani’s portfolio closely mirrors Modi’s policy priorities, beginning with infrastructure and more recently expanding into clean energy. He has thrived despite critics labeling his business empire as crony capitalism, pointing to his close ties with Modi, both as Gujarat’s chief minister – where they both hail from – and as India’s prime minister. (Like any successful businessman, Mr Adani has also forged ties with many opposition leaders, investing in their states.)

“This [the bribery allegations] is big. Mr Adani and Modi have been inseparable for a long time. This is going to influence the political economy of India,” says Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, an Indian journalist who has written extensively on the business group.

AFP

AFPThis crisis also comes as Mr Adani has spent nearly two years trying to rebuild his image after US short-seller Hindenburg Research’s 2023 report accused his conglomerate of decades of stock manipulation and fraud. Though Mr Adani denied the claims, the allegations triggered a market sell-off and an ongoing investigation by India’s market regulator, SEBI.

“Mr Adani has been trying to rehabilitate his image, and try to show that those earlier fraud allegations leveled by the Hindenburg group were not true, and his company and his businesses had actually been doing quite well. There’d been a number of new deals and investments made over the last year or so, and so this is just a body blow coming to this billionaire who had done a very good job of shaking off the potential damage of those earlier allegations,” Michael Kugelman of the Wilson Center, an American think-tank, told the BBC.

For now, raising capital at home may prove challenging for Mr Adani’s cash-guzzling projects.

“The market reaction shows how serious this is,” Ambareesh Baliga, an independent market analyst, told the BBC. “Adanis will still secure funding for their major projects, but with delays.”

AFP

AFPThe latest charges could also throw a spanner in Mr Adani’s global expansion plans. He has been already challenged in Kenya and Bangladesh over a planned takeover of an international airport and a controversial energy deal. “This [bribery charges] stops international expansion plans linked to the US,” Nirmalya Kumar, Lee Kong Chian Professor at Singapore Management University, told the BBC.

What’s next? Politically, opposition leader Rahul Gandhi has unsurprisingly called for Mr Adani’s arrest and promised to stir up parliament. “Bribing government officials in India is not news, but the amounts mentioned are staggering. I suspect the US has names of some of those who were the intended recipients. This has potential reverberations for the Indian political scene. There is more to come,” Mr Kumar believes.

Mr Adani’s team will undoubtedly assemble a top-tier legal defence. “For now, we have only the indictment, leaving much still to unfold,” says Mr Kugelman.

AFP

AFPWhile the US-India business relationship may face scrutiny, it’s unlikely to be significantly impacted, particularly given the recent $500m US deal with Mr Adani for a port project in Sri Lanka, says Mr Kugelman. Despite the serious allegations, broader US-India business ties remain strong.

“The US-India business relationship is a very large and multifaceted one. Even with these very serious allegations against someone that’s such a major player in the Indian economy, I don’t think we should overstate the impact that this could have on that relationship,” Mr Kugelman says.

Also, it’s unclear if Mr Adani can be targeted, despite the US-India extradition treaty, as it depends on whether the new administration allows the cases to proceed. Mr Baliga believes it is not doom and gloom for the Adanis. “I still do think foreign investors and banks will back them like they did post Hindenburg though, given that they are part of very important, well performing sectors of the Indian economy,” he says.

“The sense in the market is also that this will perhaps blow over and be sorted out, once the [Donald] Trump administration takes over.”